Continuing along with our exploration of East Asian music, here is a totally unique and revelatory album from China. This guy is as iconoclastic as Joseph Spence, Robbie Basho, Harry Partch, or Washington Phillips. He learned by himself, and plays for his own satisfaction. This is a music of presence, of truth and healing, not a music of glamour and show. Comparisons to Blind Willie Johnson are easy to find in the heart-turning perfection of his slides, and comparisons to Lenny Breau would not be farfetched either, for he has an equal capacity to leap into extra-dimensional territory when making melodies built of pure harmonics. But none of them sound like Lo Ka Ping. And, oddly enough, I have yet to hear any other Chinese musician who sounds at all like him either, even when playing the same instrument. The slow, entrancing music of Z.M. Dagar, the great Indian veena player (and mentor to Jody Stecher among others) would perhaps be the closest to the music that comes out of Lo Ka Ping's 7 heavenly strings. It is deliberate, suffused with microtones, and subservient to the great muse who lives in the center of the blackest part of the night sky and is the source of all dreams.

I cannot recommend this album highly enough. But be forewarned. This does not make background music. You must be ready to listen, ready to be shaken, when you play it, or all its magic will fall on deaf ears.

An album of qin music collected from archives and attics alike, comprising the whole of the known recordings of Lo Ka Ping, a lost qin master privately active before his passing in 1980. A small number of other surviving recordings were unusable due to the poor sound quality. What we have here are a number of traditional works for the qin, as well as a number of original compositions by the performer himself. Also included are two performances taken from Chinese radio around the time of the second World War and delivered to American archives by a Chinese fighter pilot. The ability displayed here by Ping is something quite worth hearing. While the recording quality tends to ebb and flow, the technique remains at a high constant level. There are other recorded qin masters available, and one should certainly avail themselves of any opportunity to pick up a number of them. Ping places himself firmly in their company with these recordings. Pick it up alongside the Hugo masters recordings, and some of the old albums on Ocora and Koch. ~ Adam Greenberg, All Music Guide

...

An album of qin music collected from archives and attics alike, comprising the whole of the known recordings of Lo Ka Ping, a lost qin master privately active before his passing in 1980. A small number of other surviving recordings were unusable due to the poor sound quality. What we have here are a number of traditional works for the qin, as well as a number of original compositions by the performer himself. Also included are two performances taken from Chinese radio around the time of the second World War and delivered to American archives by a Chinese fighter pilot. The ability displayed here by Ping is something quite worth hearing. While the recording quality tends to ebb and flow, the technique remains at a high constant level. There are other recorded qin masters available, and one should certainly avail themselves of any opportunity to pick up a number of them. Ping places himself firmly in their company with these recordings. Pick it up alongside the Hugo masters recordings, and some of the old albums on Ocora and Koch. ~ Adam GreenbergThe Wire (8/02, p.60) -

"...Lo Ka Ping was perhaps the greatest exponent of the guqin, a zither strung with seven silk chords....Lo Ka Ping's touch was deft, not a little bluesy and enormously subtle..."

...

This CD is extraordinary. Played on the guqin (an older form of the zither in China), the music is contemplative and calm and yet vigorous and austere in a subtle way...and almost indescribably beautiful and pure. By the end of the album I really did feel spiritually refreshed, baptized by sound, and I won't make this claim for even some of my favorite CDs. This quiet little album doesn't brag, but does in spades what dozens of "new age" type albums claim to do. Nothing against them, but this is the real deal when it comes to pure moods.

Lo Ka Ping, the performer (and composer of several of the tracks) was a Taoist priest as well as an English teacher in Hong Kong, and music was clearly a religious practice and exercise in self-cultivation for him, in the best tradition of the amateur literati artist. My guess is that this is what infuses the music with such a deep and mature spirituality. And in line with this tradition, he rarely performed in public as a professional would, making these recordings that much more precious.

These recordings were found in storage boxes and in attics, and the sound quality thus varies widely and, as you can well imagine, is never top notch. While a real rescue operation was performed on them sound-wise, there's only so much you can do under such circumstances. Still, this didn't distract me much, and the rarity and archival value of the recordings, along with their beauty, more than makes up for some of the fuzz and hum. The liner notes tell the whole interesting story behind this recovery as well as reprinting an article about the performer, his life and his music by Professor Dale Craig (1971) and an essay on the value of Chinese music by Lo Ka Ping himself (1920).

So if you like traditional Chinese music or are interested in Taoism and literati culture (or both, as the case may be), I can't recommend this CD highly enough. And if you're looking for a little bit of spiritual peace on a disc, I reckon you won't do much better than this.

---

Booklet notes from: http://www.arbiterrecords.com/notes/2004notes.html

Lo Ka Ping

Lost Sounds of the Tao

Accidents and chance may open doors to remarkable experiences and lost legacies. How Lo Ka Ping's recordings came to survive is one such caprice of fate. The late Teresa Sterne, who commandeered Nonesuch Records for over a decade, was a dear friend, colleague and a guiding light behind the scenes at Arbiter up until her tragic passing in 2000. She had invented and brought to fruition the idea of World Music in the late 1960's, as it then languished in a genre known as "International", a fate to which it slowly sinks once again. Those who knew Tracey were stunned by the breadth and length of her erudition: she had much to say and she said it, all! In her home, many enigmatic boxes and copious files lay about which she intended to evaluate in creating a memoir of the artists she had guided. This was not be, as illness destroyed her resilience and remarkable stamina. After she came to rest, I closely examined and prepared her archive for the various destinations specified in her testament. Her testament overlooked the fate of several tiny boxes of reel-to-reel tapes sent long ago by those hopeful of having their projects realized. Tracey once recalled a test recording made by the senior Dagar Brothers (Indian dhrupad singers) whose legacy is as small as it is of utmost significance: "They were just warming up and sang a little, not enough to publish. Too bad sweetie, I would have given it to you had I known." One palm-sized cardboard box contained music from Crete, marred by a raucous vocalizer. Another had arrived from Hong Kong, sent over by an American professor at Chung Chi College of the Chinese University. I brought these enigmatic tapes home for exploration.

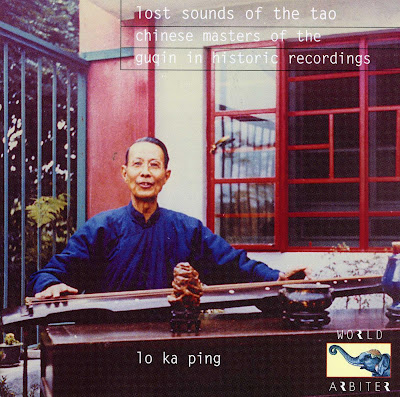

China's profound musical culture is often emarginated, as the well-known Beijing Opera presents its public side, light popular music serves as a background for daily activities. and the 'true' tradition, when offered, lacks spontaneity, the spark of life. This box contained the photo of an elderly man seated outdoors behind incense pots amidst a flurry of geometric shapes, about to caress sounds out of the qin, a rarely heard instrument (reproduced on our cover). Beneath the tiny reel of tape lay an aerogram, which read:

May 31, 1970:

Dear Miss Sterne,

In your letter of March 2 you said you might welcome an attractive program of traditional ch'in [qin] music for your "Explorer" series. I have been working on this since then and now have something tangible to present to you.

I have a tape ready of four traditional pieces (Side I) and four original pieces (Side II) for ch'in, played by an old master who lives in a country home in the New Territories. For the 'audition tape' I am sending you two of each, without documentation, romanized Chinese, or characters, all of which can be given to you later.

Included with the tape is a picture of Mr. Lo which you may want to consider for the record jacket. Photographs of his large collection of T'ang and Ming Dynasty ch'in's can also be provided (color).

My liner note information can be as lengthy (or as brief) as you like, since I am now doing research on the ch'in: notation, transcription, and analysis.

Your release of this recording would be a valuable service to the international musical community and help to broaden the range, and therefore the appeal, of your catalog offerings. Good performances on the ch'in are extremely rare at this time.

If you decide you wish to proceed with this recording, we can discuss our terms of agreement. If, however, you do not wish to go ahead with the project, I shall appreciate your returning the tape and picture to me as soon as possible.

With all best wishes -

Dale A. Craig.

We cannot know why Tracey abandoned the project, or her reasons for holding on to the tape, as she was a meticulous correspondent.How did this obscure cipher from the past play? The tape seemed able to survive a playback, so the computer was readied to digitally copy its sounds.

There emerged a vibrant expressive art, its first impression the forthright spirituality of a Blind Willie Johnson (yes, some scales have the blue note intonation!) who made his Ming Dynasty qin state and moan out visions, as panoramas of ancient brush paintings danced before my eyes, attaining life in sound, all their varied densities in depicting nature now breathing amidst sonic rainbows unleashed through the qin's harmonics. The scratching of the silk strings as one changes the finger positions is referred to as the instrument's respiration. Lo's non-thematic use of the fundamental tones in the beginning of the first piece were akin to a veena beginning a raga, causing one to wonder if this manner had become embedded in his music from the early visits by Indian Buddhists, who had brought their own instruments to China. Van Gulik [The Lore of the Chinese Lute, Tokyo, 1969, p.51] writes:

"The lute [qin] underwent Buddhist influences directly. There were many lute players among famous monks, such as, during the T'ang period, Master Ying, and, during the Sung dynasty, I-hai and Liang-y¸. When some Indian priests came to China they also brought lute-like instruments with them, and Chinese scholars studied these foreign instruments in connection with the Chinese lute. We find, e.g., that Ou-yang Hsiu, famous poet and scholar of the Sung period, praised in a poem the performance of the monk Ho-pai on an Indian stringed instrument (probably the vina).[This occurred between 1007-1072]."

Gulik elaborates in his text the ritual and self-purification involved in playing this rare instrument: "That thus playing the lute became a magical act, a ritual for communicating with mysterious powers, is, in my opinion, doubtless due to this indirect Mantrayanic influence.

"A curious result of this direct Buddhist influence is the fact that among the better known qin tunes there is one entitled Shih-t'an 'Buddhist Words', which is nothing but a Mantrayanic magic formula, a dharani. The music of this tune is decidedly Indian, vibratos and glissandos reproducing the frequent melismas used in Buddhist polyphonic chant in China and Japan up to this day. The words are also given, for the greater part in transcribed bastard Sanskrit, the usual language of dharani, and starting with the stereotyped opening formula 'Hail to the Buddha! Hail to the Law! Hail to the Community!"

Sterne's neglect in returning the recording inadvertently led to its survival, and the date of Dr. Craig's letter caused worry, as thirty-one years had elapsed and only eighteen minutes survived of a rare artist who illuminated China's musical spirit in sound.

Was there more of Lo? Where was Professor Craig? Repeated calls to his college proved fruitless, as the faculty members offered vague surmisals, that Craig had moved on nearly 30 years ago, perhaps to Western Australia. The search led onward to the remarkable ethnomusicologist Robert Garfias, based in California, who provided a lead to a former pupil now based in Taiwan, who suggested contacting Professor Kin Woon Tong in Hong Kong, one of the qin's leading experts, and to John Thompson, qin player, scholar, and researcher who created a website housing an invaluable bibliography and discography of this rare instrument, favored by Confucius.

A few phone numbers turned up and one voice reluctantly promised to contact Craig on behalf of the research. Craig phoned from California at daybreak the following day: he feared that no other recordings of Lo might have survived. Many conversations ensued and Craig mentioned the Chinese Cultural Center in San Francisco, where Craig's transcriptions and written memorabilia relating to Lo were housed. After finding their archivist, a search was made but the manuscripts deposited by Craig some eight years back seem to have been misplaced or discarded.

After listening to these 1970 recordings once again, Craig wrote: "Now I can re-affirm that he was a master who was achieving perfection in almost total isolation. After 30 years, I can take the broader view and hear how this music is related to the sitar music of India in its ornamentations and expressiveness. It is a highly-refined music and gives formal and expressive satisfaction. Aren't the "bell tones" (harmonics) wonderful?

"I found a list of the recordings I made of Lo: Returning Home, Teals Descending on the Level Sand, Phoenix on the Red Mountain, The Monk's Prayer (traditional). Composing Poems Underneath the Moonlight, The Lonely Teal, Wandering at Ease, and Meditation in the Dead of the Night (Lo's originals). They were all made in March, April and May, 1970. Four of these were on the tape I sent to your friend. Now I wonder where the other four are. I guess my wife didn't move them back to L.A. from Australia. What a loss."

Craig happened upon a forgotten 3-inch reel containing Sea Fairy and Murmuring in the Boudoir. Thompson possessed a cassette in poor audio quality made at Lo's home in 1971, with several compositions, including the Shih-t'an referred to by Gulik: only two were possible to restore, as the other pieces were sonically hopeless.

What so casually endows Lo's playing with profundity and depth is the philosophy behind the music, entering the sound through the Tao rather than displaying the fruits of a learned craft, for he was completely self-taught and thus freed from any burden of tradition. As the qin's music is notated without rhythm, he aided Craig in studying the poems and their metrics in order to decipher the music in relation to the texts on which it is based. His performances, compared to most other players, brim with vitality and spirit, like found objects emerging forth into independent existences, unlike the imposed rhythmic regularity and extremely slow tempi the works are often given by scholars. Lo was alive until 1980 (age 84): according to Tong, his family settled "either in Canada or the United States after his passing." One hopes that this disc will somehow lead to them and uncover more recordings which may survive in their private collections. Tong recalls an LP anthology of qin music on which Lo might be present, but cannot trace the disc. A group recital given at Hong Kong's City Hall in 1971 had been recorded and placed with the Chinese University' s archive of traditional music, founded by Dr. Craig:, yet they were unable to locate this document. Fortunately Dr. Craig checked his attic once again and located the taped perfomance. Craig believes it is the one time in Lo's life that he performed in public, included amidst a stream of artists who each played for a few minutes. Did Lo ever mention how he came to play the qin? Craig pondered: "No, he never mentioned why he chose the ch'in. But I think it came naturally, as a wisdom and virtue discipline, as a part of his Chinese culture. At one point I asked myself an important question: Did I choose the way of the ch'in, or did the ch'in choose me? That was probably what happened to him. I doubt that he performed publicly except in that one concert. I think he did it because of my enthusiasm and as part of our friendship, but also because he was an accomplished musician who was aging, and wanted to finally give something to a wider audience."

The following portrait written by Dr. Craig, Lo's pupil, now serves as both a memorial to his master and a grand introduction for those interested in this unique instrument whose role is bringing forth the philosophy of the Tao through sound.

In addition to Lo's surviving legacy are rare examples of scholar-performers, such as Zheng Ying Sun, and Xu Yuan Bay, all heard on restored lacquer transcription disc recordings from the mid-1940s. Zha Fuxi, a noted master, was the source of these unique examples. He had been in the United States as a high-ranking Chinese air force pilot between 1946-48: the ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger arranged to record him in Washington. The other two masters are heard thanks to discs brought over to the United States by Zha Fuxi, being transcriptions of broadcasts from Chinese radio (announced). We are aware that Zha Fuxi had been asked by Chiang Kai-Shek to become a leader in the Taiwanese air force, an offer he rejected. In gratitude, he was granted privileges by Mao Tse-Tung for his refusal: access to ancient and unique qin manuscripts, recordings, and published studies of this music were the fruit of his privileges. Fortunately, he died before the Cultural Revolution consumed China's intellectual elite and destroyed so many cultural treasures, such as these early broadcasts.. -- Allan Evans ©2001.

[from, Arts of Asia, Nov./Dec. 1971]

As one negotiates the curves of the narrow, treacherous highway from Kowloon through the mountains and farmlands of the New Territories in Hong Kong, it seems an unlikely route to a musical experience of the first order. Small herds of cows defiantly wander at leisure across the road, everywhere farmers labor in the fields, and tiny (but very tough) Hakka women in their funereal black-bordered straw hats and black pajamas carry heavy loads which dangle from both ends of their bamboo shoulder-poles.

After passing by the walled village at Kam Tin (where descendants of the original Sung dynasty villagers still live) and through Yuen Long, the most prosperous town in the New Territories, the pathway to our destination is reached. A half mile walk through sugar cane fields, and we come to a gateway with the characters for "Mr. Lo's English Academy".

We ring the bell, and soon Lo himself, a gentleman in his seventies, comes to welcome us. We stroll past barking dogs, roosters perpetually announcing dawn, and a scampering pet monkey; then we pass one or two miniature rock gardens built by Mr. Lo himself and enter the living room, where Chinese folk instruments such as the san syan three-stringed banjo, ban hu and ye hu, coconut-shell violins, and chin chin, middle-range guitar, hang from the walls.

Upon finishing some earthy lok-on tea we are escorted through a large classroom lined with zoological specimens such as cats, frogs, and snakes preserved in jars. In the old-style dining room with its marble table and large carved chairs, there are many paintings and fine examples of calligraphy scrolls, and a valuable gu qin (qin or ancient zither), the first of many to be found in Lo's home.

Upstairs we are shown the Taoist meeting-hall. Lo is not only a qin player and composer, teacher of English, school administrator, and village government official; he is a devout Taoist, an author of several tracts, and leads his own sect. As we observe the altar with its smouldering incense and offerings of oranges and bananas, we remember the many testimonials to Lo's healing powers, still in his possession, from his followers (both European and Chinese) in Canton. He believes that Heaven has granted him the power to learn anything he wishes, and, since he taught himself the extremely difficult art of playing the qin, we come to understand his faith.

Now we are admitted into the inner sanctum: Lo's studio. T'ang, Sung, and Ming qin's all in excellent condition since they are played almost every day, are all around us. I note that a favorite, named "Jade tinkling in high heaven", rests on the playing table. A little jade box containing Lo's complete repertoire- each title on a separate cardboard disc- sits behind the qin, along with an incense pot and a few green plants. At one time he knew fifty traditional pieces, now can still play fifteen from memory. In addition he remembers fifteen of his original compositions.

Before he plays for us he invariably closes his eyes (gaining composure and perhaps uttering a short silent prayer) and clears his throat. As he begins the traditional piece "Returning Home", one is struck by the character and virility in his playing. Rather than finesse and elegance, such as a master from Soochow might display, his playing has more of Cantonese soulfulness and forthrighness. He is capable of continuing for as long as one cares to listen and obviously takes an intense delight in performing.

The sound of the qin, for those who are unfamiliar with it, is, by comparison with most other instruments, muted and grey. This austere quality is perfect for its use as a conveyor of quiet, introspective moods. It probably has the softest tone of any instrument in existence, and it takes some time for one's ear to adjust to its level of sound and begin to enjoy it on its own terms. Its subdued sound makes it suitable for intimate and private performances-like the Western clavichord. Once one has entered its sound-world, however, one begins to distinguish between the various subtle and very special fingerstrokes and ornaments, all of which are fixed by convention and precisely described in handbooks. The frequently-heard harmonics (made by touching the string lightly with the left hand rather than pressing down firmly) are particularly beautiful; they ring like tiny, unearthly bells.

As we listen to this quiet music, we try to achieve a state of serene contemplation such as all the qin masters advocated. We might, as a help, remember the beginning of the Poetical Essay on the Lute, written by Hsi K'ang, who lived from 223 to 262 A.D.: "From the days of my youth I loved music, and I have practised it ever since. For it appears to me that while things have their rise and decay, only music never changes; and while in the end one is satiated by all flavors, one is never tired of music. It is a means for guiding and nurturing the spirit, and for elevating and harmonizing the emotions. . ."

After Lo has played, he chats with us about the centers of fine qin performance in China, speculating that even in contemporary China areas of such intense, specialized, and renowned musical activity perhaps still produce expert qin players. They are Peking in Hopei province; Nanking, Soochow, and Yangchow in Kiangsu province; Taiyuan in Shansi province; Changsha in Hunan province; Canton in Kwangtung province; and Taiwan. Musical societies in each of these centers issued important publications and helped maintain high musical standards.

The experience of visiting a musician such as Lo and hearing him play is an extremely valuable, because so rare, in present-day Hong Kong. He is one of the very few qin players of any skill in the colony, and in addition is an authentic representative of a very special type which is almost extinct outside China (and, after the Cultural Revolution, perhaps inside China as well): the gentleman-scholar who is also an excellent amateur musician, so evocatively described in R.H. van Gulik's The Lore of the Chinese Lute. Originally published by Sophia University in Tokyo in 1940, this masterpiece of scholarship has ben recently been re-issued by Charles E. Tuttle Co. in a new edition [sadly out of print soon after its reprinting in 1968- ed.].

Lo never depended on playing or teaching music for his livelihood, as do virtually all other musicians in Hong Kong where the present situation of Chinese music is disastrous. Most of the better musicians have to play dinner music in the large hotels by evening or teach in the middle school and privately by day, or both. The purely commercial society of Hong Kong only seems to have a place for diluted Chinese "classical" music and semi-popular or outrightly commercial new compositions and arrangements. The government has taken no steps to preserve genuine Chinese cultivated music, and it is in danger of disappearing entirely.

Lo Ka Ping's career is deceptively prosaic, when we consider that he was born during the Ch'ing dynasty and lived through all the cataclysmic events of twentieth - century China. And his present life-style is a tribute to the tenacity of the Confucian tradition in the modern Chinese mind. Born in Canton on February 22, 1896, he graduated from the Ling Nam University when he was 22. He was an early spokesman for the value of Chinese music as part of a modern education, The title of one of his lectures, "Should Chinese Music be Taught in Christian Schools" (1920, reproduced following this essay), is indicative of the condescension of his listeners at that time.

From 1917-24 he taught English in several Kwantung middle schools, and in the following years was first an Inspector of Schools and then the Head of the Education Department of a district. He served for two years in the Militia Council of the Nationalist Government as a Major, and was on the teaching staff of the Sun Yat Sen University. 1929-35 was spent as Headmaster of several middle schools, in Singapore as well as Canton.

Lo passed the [Second World War] years in Macao, where he taught English and authored a textbook, and when the war was over he came to Hong Kong. He held teaching posts in government schools in Yuen Long and was Headmaster of two other schools in the New Territories and in 1964 he became the Principal of his own school where he now lives. In 1969, when he was 73, he retired from teaching, after a trip to the United States, though in the world of music he is still very active both as a player and collector of the qin.

The story of the qin is nearly as old as that of China itself. The earliest definite references appear in the Book of Odes during the Western Chou period (1122-770 B.C.). At that time the qin already had seven strings, and was frequently used in combination with the se, a larger instrument of 25-30 strings.

Both the qin and the se are in long zither shape, but their construction is completely different. The se, from which the later instrument chang was derived, is a psaltery. That is, the strings have bridges and are plucked. The body of the se is hollow and gently convex. It was a good orchestral instrument because of its large volume of tone.

The qin is made from an upper convex board of ting wood and a lower flat board of tzu wood. In the middle of the back is a sound hole traditionally called the dragon pond; closer to the player's left is another resonance hole known as the phoenix pool. Two anchor knobs are used to secure the silk or nylon strings. The strings are wound around the anchor knobs, the tuned exactly with the tuning pegs from which hang tassels.

The qin and se were used in Confucian ceremonial orchestras to accompany singers and as solo instruments. Throughout its history the qin has been associated with nobility and refinement, and an ability to play it, or at least deeply appreciate its music, was considered indispensable for any scholar or cultured person. It is frequently referred to in literature as the most poetic and subtle of all instruments. Confucius was one of the most famous players and composers for the solo instrument.

It is indigenous to China, and is perhaps the most peculiarly Chinese of all Chinese instruments. An ideology grew up around the qin as the dynasties passed, eventually encompassing, in addition to many other rules, the circumstances in which it should be played: there should be fine scenery, one should ideally have bathed before playing the qin, one should play under pines with cranes stalking nearby if possible, and so on. Qin music is full of references to nature, and ideally a fine player should conjure up images of nature in a sympathetic listener's mind.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the qin is its elaborate and difficult notation, which goes a long way toward conveying the complexity of the music itself. This notation is in special Chinese characters which are a kind of tablature, i.e. only the finger positions, type of stroke, which string to be played, and the ornamentation are shown. Pitch is not shown directly, and rhythm is not shown at all, since ideally each player is to create his own rhythmic values! (In practice, meter, tempo and rhythm are usually learned from one's teacher by rote).

Just as the repertoire of a pianist or violinist tells everything about his musical taste, so it is for a qin performer. Lo's favorite pieces are usually quite difficult and lengthy and invariably express a lofty sentiment. A representative sampling would include: Conversation between the Fisherman and the Woodcutter, Phoenix on the Red Mountain, The Monk's Prayer, Teals Flying Over Heng Yang, Sea Fairy, The Mongolian Trumpet composed by Tung T'ing-lan of the T'ang dynasty and Clouds over the Hsiao and Hsiang rivers composed by Kuo Mien of the Sung dynasty.

Like many Western composers, Lo claims he composes best late at night, in the clarity of solitude. He has never dared to drive an automobile, because when a melody comes to him, it possesses him and he can think of nothing else. Some of his longest works were composed only in two or three days. His compositions are technically advanced, show strength and individuality, and demonstrate a capacity for extended structures which is, of course, largely intuitive. Some of his favorite original compositions are: The Lonely Teal, Composing Poems Underneath the Moonlight, The Dream of the Maid in the Distant Tower, Meditation in the Dead of the Night and Wandering at Ease.

Several of these compositions were heard in Lo's solo performance and in orchestral arrangement in the recent symposium "Chinese Music: Past, Present, and Future" presented in Hong Kong City Hall on October 5th, 6th, and 7th [1971] by the Music Department of Chung Chi College in the Chinese University of Hong Kong. These performances confirmed our opinion that his entire output should be carefully studied and preserved.

After examining the milieu and life-style of this English teacher from Canton whose outward career has appeared so ordinary, one comes to appreciate his astonishing consistency and unity of purpose. Every object, painting, book, carving, or instrument in his home complements every other and bears witness to his integrity and high ideals. His Taoism makes his music possible, and music is indispensable in his Taoist ceremonies. His is a home in which music naturally flourishes. That it has flourished is evident in his poised and subtle compositions and his skillful and inspired performances. -- Dr. Dale Allan Craig, Hong Kong, 1970.

Should Chinese Music Be Taught In Christian Schools?

by Philip Lo [Lo Ka Ping], 1920

It is with very profound pleasure that I meet you all here to-night. I have been an interested listener to the various speeches that have been delivered by musicians on this auspicious occasion and I assure you that I have derived very material assistance from the suggestions advocated. But, in particular, I am requested to make a few remarks on a special phase of the subject. I feel very incompetent, however, to speak clearly on such an intricate and perplexing topic as that on which I am asked to speak. When I consider the qualifications of my audience, I can hardly have enough nerve to get up to this platform. Not having learned the art systematically, I can scarcely add any embellishments to the discussion. Indeed the few pieces that I am able to play have been learned at random and only by blind imitation. But since I am given the honor to speak, I feel it a duty to lay bare my few scanty thoughts on Chinese music.

Before answering the questions - "Should Chinese music be taught in Christian Schools?, it is well, I think, to examine into the cardinal purposes of Chinese music as conceived and practised by the fathers of the art. The chief of these was the purification of the sensual impulses. Our fathers believed that music had the power to rouse the beast-like emotions and thereby drive them away, thus purifying the heart. This, it is to be noted, is in facsimile with the Aristotelian conception of the purpose of music, a conception which led him to advocate that music be incorporated into the school curriculum. Secondly, they intended and actually used music for the psychological examination of human nature. They recognized over two thousand years ago that the native constitutions of human beings possessed both good and bad traits. By the proper exercise of the one and judicious suppression of the other, the child could be moulded to be a good citizen. They claimed that by playing a certain kind of music in the presence of a child, he would invariably respond in a certain way as indicated by his facial expressions. This experiment could be carried out, of course, only by expert musicians. Last, but by no means least, our fathers believed that the person playing music at a particular time indicated his state of mind at that time, such as fear, anger, or happiness. Numerous instances can be cited from our history as illustrations of this point. One of these, I suppose, would suffice. Those of you who are acquainted with the history of ancient China know the great general and far-sighted statesman Hung-ming. Once he planned a defensive attack, but through sheer insanity and total lack of common sense of the man he placed in charge of the scheme, his forces were annihilated. The enemies drew near the city. He realized his danger of being captured unless some ingenious plan be instantaneously devised. This he did by getting up to the top of the highest building and there concealed his fear of the approaching by playing a Chinese Seven-stringed Harp, from the sound of which it seemed that he was very joyful and contented.. The adviser of the enemy listening carefully to the songs, detected that it was a fake, but the generalissimo refused to take the advice and withdrew his forces immediately. Thus Hung-ming was saved.

From this brief enumeration we indubitably see that morally, psychologic[ally], Chinese music is an art. That this is so was upheld by our greatest sage Confucius. He believed that no man's education could be considered complete without a sound knowledge of music. That is why he included it among the six fundamental branches of study. The character of its inventors seems to substantiate this dignified appraisal, being invented by men of high intellectual calibre, among whom were philosophers, prophets, kings and emperors. Specifically the Seven-stringed harp, the most beautiful of all our musical instruments, was invented by Fu-hie, who was our emperor. Of course I do not assume that all emperors had inventive ability. But in this particular case, noble rank was coupled with exceptional ability.

Just as its inventors were men of high intelligence, so too, were the men who practiced it. In olden times no ordinary man dared to practice this noble art. We are bewildered to find that this is the exact reverse today. But the cause is not to [. . .]. As with everything else, glory is always followed by decline. When music had reached its peak, of glory, it began to deteriorate. Soon, men [from all] scales of social and intellectual development tried to master the essentials which made music what it was at first, its true beauty was gradually lost. In turn this is due to the lack of [a] universal system of instruction. At the beginning and for a long time afterwards, the musicians had a great deal of leisure, as they were mostly men who lived in retirement. These men had plenty of time to improve the instruments and composed songs for themselves. But they left behind no records of their methods.

This long decay through promiscuous practice and lack of instruction makes music appear today very different from what it was. We now find an enormous [. . .] of musical instruments, a great many of which [are] being played by persons way down in the social scale. This does not mean, however, that the instruments themselves are inherently bad. Nay, their ignoble appearance has been given them temporarily by their unworthy practitioners. This fact clearly points to the pressing necessity of thorough reformation and judicious selection. To this end I have formed an association of Chinese musicians, which meets regularly once a week. In endeavoring to bring about this reorganization, we are trying at the same time to work our a scientific method of teaching. With all the intricacies involved, such a work cannot be accomplished all at once. But although it is still in process of discussion, yet our efforts thus far have been amply gratified by discovering many instruments that deserve to rank among the highest of musical instruments. A few of these I have roughly sketched and, if you are interested to know what they are, I shall be very glad to show them to you at the conclusion of the meeting.

I have given you the facts and opinions of Chinese music and I shall be very glad if a step be taken to make it part of the curricula of Christian schools. If it could purify the heart by arousing and driving away the sensual impulses; if it could detect the weak points in this active constitution of the child; if it could show the state of a person's mind at any time; then it would accomplish a great part of what morality, psychology, and education strive to accomplish in concurrence. As such, it should be made part and parcel of all school curricula.

All notes and translations © Allan Evans.

Lo Ka Ping - Lost Sounds of the Tao

Label: World Arbiter #2004

Year: 2002

Lo Ka Ping, guqin. recorded 1970, 1971

Tracks:

1. Teals Descending on the Level Sand

2. Returning Home

3. Composing Poems Beneath the Moonlight

4. Lonely Teal

5. Water Spirit

6. Murmuring in the Boudoir

7. Water Spirit

8. Buddhist (Shih-T'An) Stanza

9. Teals Descending on the Level Sand

10. Meditation in the Dead of the Night

11. Empress' Lament

12. Conversation Between a Fisherman and A Woodcutter

* there is an unfortunate digital skip towards the end of track 11, and track 12 is missing. If you want a clean version, please buy the CD from World Arbiter.

I believe I have this album thanks to Lemmy Caution. Thanks Lemmy!

.jpg)